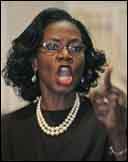

Another now-former city official, Chicago 20th Ward Alderman Arenda Troutman (shown left), was caught up in a federal public corruption sting. In Chicago, city council members are called aldermen; their districts are called wards. On Feburary 9, 2009, Troutman was sentenced to 48 months in federal prison for mail fraud and tax fraud.

Another now-former city official, Chicago 20th Ward Alderman Arenda Troutman (shown left), was caught up in a federal public corruption sting. In Chicago, city council members are called aldermen; their districts are called wards. On Feburary 9, 2009, Troutman was sentenced to 48 months in federal prison for mail fraud and tax fraud.

Sometimes people ask why so many corruption prosecutions are federal rather than local. It’s a good question.

A good place to start is with the crimes for which Troutman was convicted. According to the Internal Revenue Service, as part of her plea agreement Troutman admitted:

- She solicited payments and other things of value from persons who sought her support for a specific land use, zoning change, or alley access;

- She used her official position to coerce $21,500 in kickbacks from developers to support their projects in her south side ward and in one case outside her ward;

- She made it clear that her support for the developer’s project would either not be forthcoming or would be delayed if she was not paid;

- She failed to report as other income on her tax return, at least $10,000 in cash that she received; and

- She also listed her total income as being $77,801, when it was actually substantially more than that.

There are more colorful details in the August 6, 2008, Chicago Sun-Times online article by Natasha Korecki Former Ald. Arenda Troutman pleads guilty. Only somewhat less descriptive was the Chicago Tribune‘s August 6, 2008, online article by By Dan Mihalopoulos and Jeff Coen. The Trib’s article was captioned Ex-alderman pleads guilty to fraud charges.

So the question remains, why are so many of the public corruption crimes prosecuted federally? Isn’t the public corruption of local officials really a local matter? Shouldn’t local authorities be investigating and, when warranted, prosecuting corrupt local officials?

Yes. Local investigation and prosecution is exactly what should be happening. The Chicago Police Department or the Illinois State Police should have been the ones investigating Troutman. The Cook County State’s Attorney or the Illinois Attorney General should have been the ones going forward with the prosecution. Unfortunately, there are reasons why local authorities can’t or won’t fulfill their duty and obligation to protect the people in their communities.

First, many state and local law enforcement agencies do not have the expertise or the resources to conduct long-term undercover investigations of complex financial crimes. These can be intricate and time-consuming financial investigations sometimes needing to identify proceeds hidden out of state or out of country. What can start out as an apparently straightforward investigation into one official’s bribery can evolve into interrelated crimes beyond the reach of state statutes and local public safety budgets.

Second, many state and local law enforcement agencies do not have the political will to investigate officials in city halls, county halls of administration, and state capitals. They would end up investigating the very people who oversee their agencies’ budgets and sign their paychecks.

Third, some state legislatures do not see public corruption as a particularly serious problem. That is reflected in the laws they pass with comparatively trivial penalties upon conviction. The legislators may harrumph and bluster against bribery and corruption when they’re spreading fertilizer on the folks back home, but when it comes down to it, they really don’t want to pass laws with enforcement provisions that could come back to haunt or hurt them or their major campaign supporters.

Fourth, elected prosecutors may not have the legal or factual basis to prosecute complex public corruption cases. A prosecutor can only bring prosecution for the laws provided by the legislature and go with the case he’s given by the investigators. No prosecutor should go forward with a prosecution if the investigation was so poor that a conviction is unlikely.

Fifth, elected prosecutors sometimes do the financial calculations before bringing cases against public officials. One factor in that calculation includes the cost to the public to prosecute a weak case or one likely to result in a meaningless penalty upon conviction. Another factor sometimes considered is the effect a prosecution might have on those who donate heavily to political campaigns. When a prosecutor’s biggest donors and supporters also support the most crooked officials and profit from their illegal actions, it can be a difficult decision.

Sixth, some crimes are exclusively federal jurisdiction. For example, only the Internal Revenue Service can investigate and pursue alleged violations of the Internal Revenue Code.

A federal investigation and prosecution is not automatically the best and final solution to the weaknesses mentioned. As we saw in the Bernard Madoff fraud, there are indications that the Securities and Exchange Commission may have done more than dropped the ball; it may have helped to hide it. Still, the further one gets from the hemorrhoid of corruption (city hall, county hall of administration, state capital), the less likely it will be that well-connected local officials will be able to squelch investigations or influence decisions to charge and prosecute. While we wish local law enforcement and prosecutors had the will and the skill to do the job, the reality is that at times they don’t.

The feds do have better things to do than go after crooks like former Alderman Troutman who derisively referred to her fellow Chicago aldermen as “ho’s”. The bribes she received appear to be chump change when compared to one of her alleged boyfriend’s drug transactions. But when local law enforcement and prosecutors can’t or won’t act and when federal laws have been broken, it is appropriate for the federal agencies to step in to protect the citizens in the communities. That’s what we pay federal taxes for.

Wow. Elected officials who have approval over developments getting paid by those developers. Where have we seen that before? Shall I upload a PDF copy of a conflict of interest disclosure?

Comment by Dan — April 15, 2009 @ 11:44 am

The state prison doesn’t have tennis courts and putting greens and if you are in the know you know the country club is the place to be

Comment by casper — April 15, 2009 @ 5:00 pm